Good Times / Bad Times

In 1985, when I was 21 years old, I wrote to the author James Kirkwood. I had recently devoured his novels, There Must Be A Pony!, Good Times/Bad Times, Hit Me with a Rainbow, and P.S. Your Cat Is Dead, and I just had to make contact with this literary genius all the way on the other side of North America in some place otherworldly like New York. I remember I wrote out my letter longhand, then typed it on my father’s Remington Steele. I couldn’t imagine that someone as important as James Kirkwood, who had also won a Pulitzer Prize for co-authoring “A Chorus Line,” would actually write back to me, but that’s exactly what he did—on November 16, 1985.

“What a wild last name you have,” his letter began (although he also misspelled it, “Gadjics”), after which he thanked me for writing. I loved that the “W” dropped at various places throughout his typewritten letter—a sign of the times, like a reminder of our frailty, that’s since been lost to the uniformity (and monotony) of computers. I can’t remember much of my letter, but I must have said something about my conflicted feelings around sex, or sexuality, or identity, because in his third paragraph, Kirkwood wrote:

“Everyone has identity crises, but just remember no matter what’s going on in the outside world, it’s our task to create our own happiness. I think we should do everything possible to not expect outside influences to provide joy—although at times, they certainly do. Day by day, we should try to figure out how lucky we are to be alive and (relatively) sane.”

I also must have told him that I was an aspiring writer, because he closed the letter by encouraging me to:

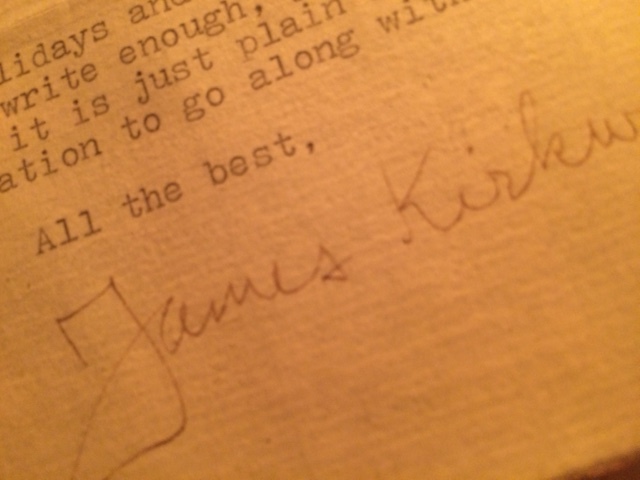

“. . . press on with your writing career. If you want to write enough, you can write. I really do believe a lot of it is just plain will power, as long as you have the imagination to go along with it.”

His words couldn’t have been truer—especially around the will power. Somewhere between my 300th and 500th rejection for my first book, The Inheritance of Shame, I felt like I was being devoured by rabid dogs, although it’s not so much that I wanted to give up as I thought I wasn’t going to make it to morning. Rejections, I’ve learned, sort of feel like being annihilated, bit by literary bit, and I guess it’s true that what’s largely kept me going is this thing called “will power”—some higher, or deeper, belief or desire that transcends words but that also picks me up and sends me on my way come morning. Life wants to keep living.

Kirkwood’s letter was so deeply inspiring to me that I wrote him again—about two years later, after a few of my poems had been published in my college newspaper, and my first one-act play, “Killing Maggie Cat,” had been filmed for community television (with me directing). As this was long before the days of computers, and I was never a fan of smudgy carbon copies, I did not keep a copy of my letter; but in his response, dated January 24, 1988, he does quote part of my own letter back to me: “I love the sentence,” he writes about my own words, “‘When I read your books, I feel like there is one other person in the world that has understood . . . what has made me sad.’” I can’t quite remember what made me sad in 1988, other than life in general and the daily toll of trying to live as a heterosexual when I knew that none of my family would ever accept me for who I really was: a homosexual. But Kirkwood’s comments brightened my life immensely, and he even went on to tell me about his current writing projects, a novel that I understand was never published, called I Teach Flying, and (as he wrote) “. . . another play which has been optioned called ‘Stagestruck,’ and I am also half way through a nonfiction book to be called Diary of a Mad Playwright.” His closing has always warmed my heart:

“So you keep all your crossables crossed for me and I’ll do the same for you and I’ll be in Scotland afore ye. A warm embrace—”

For the next few years, as things went from bad to worse for me, I imagined that any time soon I would fly to New York and arrive on his doorstep, since his address was right in the header of his letters, and we would become lifelong lovers. Inseparable. This was long before the days of celebrity stalking, and my fantasies had less to do with him being famous than it did with finally connecting with another human being who seemed to understand my struggles.

When I learned that Kirkwood had died of AIDS, years later, it broke my heart. I couldn’t talk about his letters to anyone, because I knew that if I did I’d start to cry. So many talented artists, so many human beings generally, wiped out by a tragic illness made all the worse by ignorance and hatred. I still feel like crying when I think about it, and also how close I came to becoming a statistic myself. The pain of it all is sometimes still too sharp to contemplate, so I mostly keep the memory at a safe distance. But when I look at Kirkwood’s letters now, as I do from time to time, framed and hanging close to where I write each early morning, and late every night, I think of him and his kindness. He told me that my “warm words” were “very encouraging” to him; and yet it is his words that swim back to me today and each day, decades letter, encouraging me to “press on.”

“If you want to write enough, you can write . . . a lot of it is just plain will power, as long as you have the imagination to go along with it.”